Jonathon Delacour has an interesting writing on appropriation art, the controversy about the Obama HOPE poster, and Walker Evans. I must admit to being mostly ignorant about appropriation art, where the artist takes another work and either creates a variation of the work, as Shepard Fairey did with the HOPE poster; or actually makes a direct copy of a work, as Sherrie Levine did by taking photos of Walker Evans public domain photos, claiming the works as her own, and then applying her own copyright.

Leaving aside all other issues, the legality of such appropriation is based on whether the new work is derivative or transformative. For instance, Picasso is consider an early appropriation artist, because he would appropriate things he found in the everyday world for his work. However, the materials Picasso appropriated were not works of art themselves, but everyday things that he would then transform into original creations of art. I had an uncle, heavily inspired by Picasso, who was also an appropriation artist, as he would take clothes hangers, paper, and paint, and create statues—one of which I, in the midst of my plebeian youth, threw away, thinking it junk.

I suppose that Fairey’s work could be considering transformative, too, as he took a photograph and transformed it into a painted, or more likely photoshopped, effort. Tom Gralish is the person who helped uncover the original photo behind the transformed work, and as the images he display demonstrate, Fairey used the same technique more than once with more than one photographer’s effort.

The AP, who hired the photographer, Mannie Garcia, to take the photo used in the HOPE poster, disagrees that the “appropriation” of the photo is fair use, and have contacted Fairey to make arrangements (though there is some debate that the AP does own the photo copyright). It would seem that Fairey, himself, didn’t even know whose image it was he used until he was contacted. I found his ignorance of the original photographer to not only be offensive, but sublimely arrogant. If one is going to appropriate another artist’s work, shouldn’t one at least take a moment to discover the name of the artist? Evidently, to Fairey, not. To Garcia, his photograph is art; to Fairey, it’s raw material, the equivalent of a coat hanger.

I am not an expert in copyright law to know whether Fairey’s work is a violation or not, nor am I necessarily in sympathy with the AP, though I will watch the ongoing story with interest. However, I don’t have to be a lawyer to know that Sherrie Levine’s appropriation of Walker Evans work is legal, but morally reprehensible.

In Levine’s case, she took photographs of Walker Evans photos that were in the public domain, printed them out for a show titled After Walker Evans, and then copyrighted her photographs of the photographs. Since the Evans photos were in the public domain, she could do what she wanted with the images.

I gather, according to Jonathon, she had some postmodern feminist story to accompany the work that sounded all grand and really brainy, I’m sure, but strip away all the mental cotton candy and what you’re left with is a photographer exactly duplicating another photographer’s work, and then attaching her name to it.

Applaud, the postmodern Athena is avenged on the paternalist Zeus. As others have written, Levine’s disrespect for paternal authority suggests that her activity is less one of appropriation: she expropriates the appropriators. How could I, as a feminist, not applaud such an act?

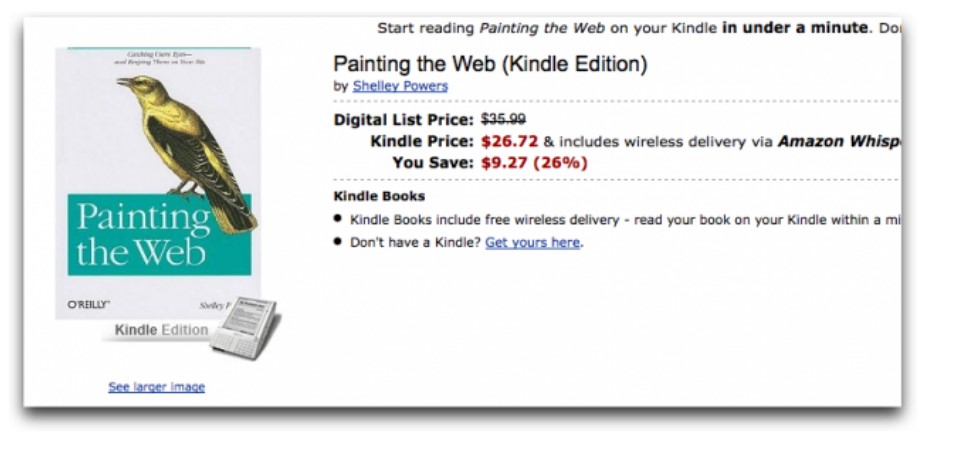

What if we were not talking about visual art, though? What if I were to take a work by another representative of paternal authority, Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, type it exactly as written into my computer, sign my name as writer, convert the document into Amazon’s Kindle format, copyright the effort, and sell it at Amazon? According to both Levine’s viewpoint and this modern variation of appropriation artists, not only would such be acceptable, I should be praised

In 1979 in Sherrie Levine rephotographed Walker Evans’ photographs from the exhibition catalog “First and Last.” Her post-modern assertion that one could rephotograph an image and create something new in the process, critiques the modernist notion of originality (though it creates an alternate postmodern originality in the process.) In dialogue with the theorist Walter Benjamin, who explored the relationship of reproduction to artistic authenticity, the reproduction becomes the authentic experience.

Yet, it is likely that those who would praise Levin and her work, would condemn me and mine. She is artist, I am vile plagiarist. A plagiarist easily caught, because the original story is so well known.

If the work of Twain is too well known to be vanquished by a single act of unattributed duplication, then what of our replication of syndication feeds, or weblog posts? The casual page such as those I quote from in this story? Would our writing not be like Mannie Garcia’s photo, in the public sphere but not well known enough to have self-defense against such deception?

I don’t know of any writer who would willingly allow their writing to be duplicated and attributed to another, without even a semblance of a nod to the originator, but we don’t have the same problem with visual works, such as photographs. As Jonathon states, We are in a hall of mirrors, but mirrors that shatter with text. If one can’t take the concept from one artistic medium to the next, then the concept is suspect, the art tainted.