I am not a Walker Evans expert, but from my recent readings about him, I sensed there were three significant events in his life that shaped the man, and subsequently, the photographs we’ve come to cherish.

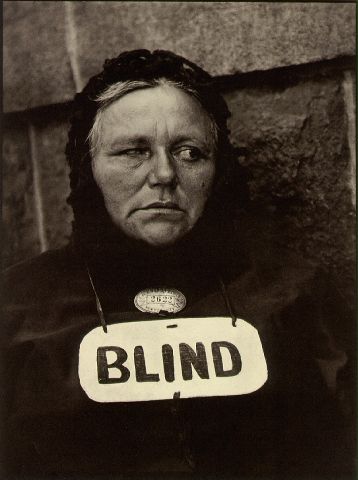

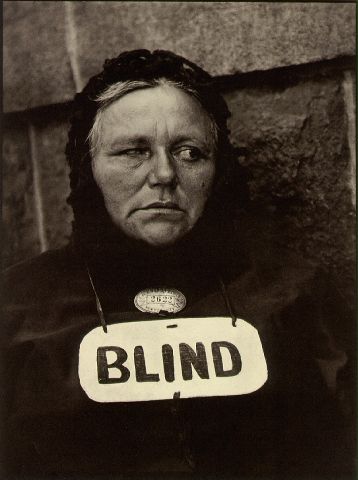

One of the events I briefly mentioned in the last Walker Evans writing, and that was his search for a particular style of photography. Rejecting the existing photographic styles of the time– which either disregarded the strengths of the camera in favor of artificially created scenes, or sought to tug emotion from the viewer–Evans sat in a library looking through all 50 issues of the photographic journal, Camera Work until finding what he was looking for: Paul Strand’s photograph of a blind woman, shown below.

In this picture, Evans saw an uncompromising realism unfettered by any emotional hooks. There was no attempt to make the woman into something either to be admired or pitied; nor was there an attempt to make a ‘pretty’ picture, or a noble one. Combined, this realism and lack of emotionality formed the basis for Evans’ own style of photography: unsentimental, realistic, and unstaged. In other words: objective.

A search for objective truth in art wasn’t unique to Evans–many of the creative people of that time shared this philosophy about their work. But objectivity was almost an obsession with Evans, and we can trace the roots of this to his upbringing and the second pivotal event in his life: the separation of his parents when he was in his teens.

Evans came from a relatively affluent family, and his father was a prominent marketing and advertising man, a profession Evans was later to term one of the bastard professions. His mother was from a wealthy family and liked nothing more than to be a figure in society.

Evans had a relatively happy childhood until they moved from his home near Chicago to Ohio when his father got a new job. It was in Ohio that his father began an affair and subsequently left his mother. Evans, already lonely from the loss of his childhood friends was left confused and unsure, and the previously outgoing boy began to draw inwards, away from his contentious family.

His mother, whose world was drastically upset, begin to live vicariously through her children, determined that they were going to have happy, prosperous lives (with her a central part in each). She was, in many ways, an outwardly sentimental woman, but at the same time, she was not demonstrative or terribly affectionate.

Within the Evans family, before and after the separation, sentiment was both an artificial promise and a means to an end. Through his father, Evans saw sentiment used as a tool to lure people into buying a product or service: after all, what better way to build a successful advertising campaign than to incorporate images of cute babies, small puppies, and happy American families. From his mother, Evans perceived sentiment woven into a complex fabric consisting partially of denied security and affection, a great deal of manipulative guilt, and even some frustrated sexuality.

Though it’s not as fashionable to lay praise for a person on their early childhood experiences, it’s difficult to deny the impact Evans’ parent’s separation, and their behavior both before and after, had on his search for both objectivity, and anonymity, in his work.

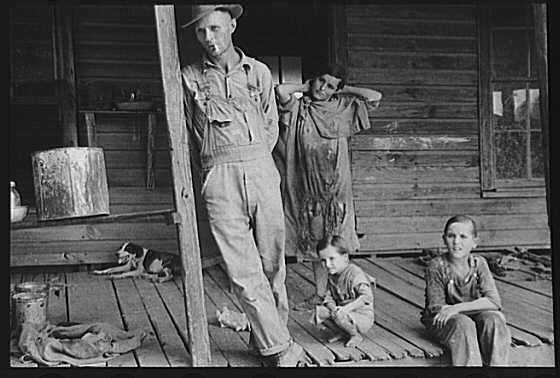

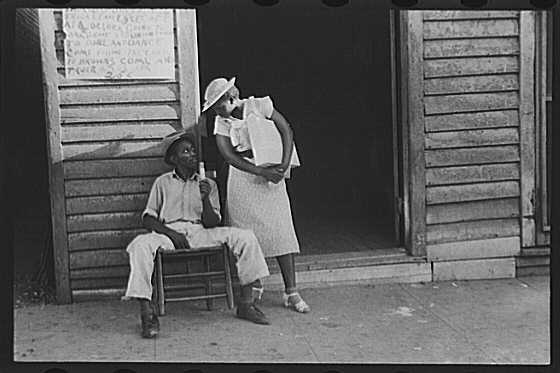

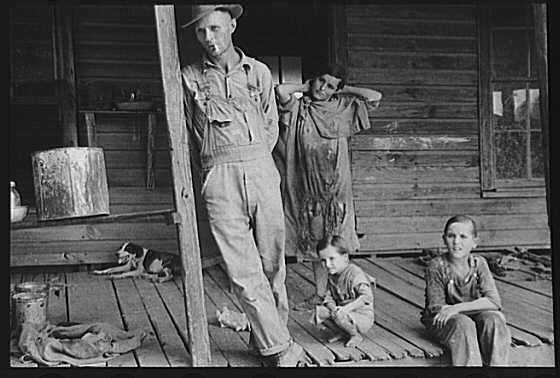

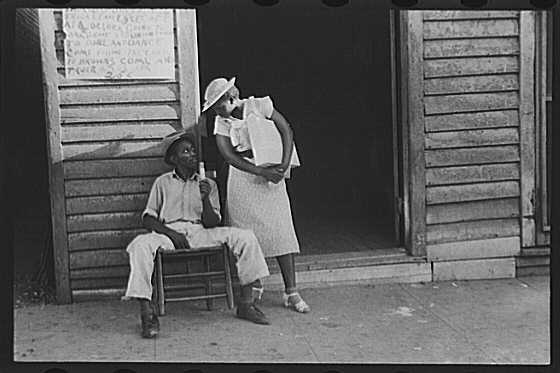

To get a better understanding of Evans’ objectivity, compare his photographs of sharecroppers during the Great Depression with those of another very famous photographer of the time: Margaret Bourke-White.

A month before James Agee and Walker Evans took off on their trip that would result in the book, Now Let Us Praise Famous Men, Bourke-White took off for similar reasons with the well-known writer, Erksine Caldwell.

Margaret Bourke-White was not a person who waited for a photograph to happen. Whenever they arrived at a potential scene, she would direct the people, telling them not only where to stand but what type of emotion to display on their faces. From Belinda Rathbone’s biography of Walker Evans:

White relied on Caldwell to guide her to the people she wanted to photograph, but once there she went to work “like a motion picture director”, remembered Caldwell, telling people where to sit, where to stand, and waiting for a look of worry or despair to cross their faces. Under her direction, passive, weatherbeaten, and cross-eyed sharecroppers were turned into characters in a play, playing themselves.

Bourke-White even went so far as to arrange objects in a scene, for which she was scolded by her co-author (and husband), Caldwell. Unusual behavior considering the following quote:

I feel that utter truth is essential,” Bourke-White said of her work, “and to get that truth may take a lot of searching and long hours

Bourke-White would enter churches during services and start taking pictures, once going so far as to climb in through a window one time when she found the door locked during a service.

Evans, on the other hand, was reluctant to intrude. Rather than ask to enter a church, he would take photos of the outside. He wouldn’t touch any objects within a scene, and when taking pictures of people, he would allow them to pose themselves, or he would wait to take the picture until their initial stiffness from being in front of the camera wore off.

More importantly, he refused to make the people into objects of pity, which, after all, would imply sentimentality. If Bourke-White’s photos inspired one to want to change the fate of the people, Evans inspired no such humanitarian impulses. One never feels guilt, when looking at an Evans’ photo. Or pity, or humor, or desire. All one feels is interest, admiration, sometimes astonishment…and a little envy, but that doesn’t arise from the subject.

So what was the third event that was so significant in Evans life? Well, in actuality it was a non-event.

When Evans was a young man, he convinced his family to send him to Paris to study the language and literature. At that time, photography was only a hobby for him, he wanted to be a writer. And there was no better time for an aspiring writer to be in Paris, with the likes Ernest Hemingway, T. S. Eliot, Dorothy Parker, Ezra Pound, and someone whom Evans admired above all others, James Joyce, living there.

Evans would hang out at the bookshop where Joyce would appear every day, watching other young men and women seek Joyce’s company, to shake his hand and try to engage him in conversation–an impossible task with the monosyllabic Joyce. The shop owner offered an introduction between Evans and Joyce, but Evans shied away from his chance to meet his hero, something that he’d talk about for many years into the future.

When Evans returned to New York at the end of the year, photography gradually overcame his interest in writing, inspired in part, I believe, by James Joyce. After all, what could Evans write that had not been written by others such as Joyce? And how could he shine in a field as luminous as this? All those who write experience these moments of doubt when we read another’s writing that is so brilliant that we are left feeling humbled and inadequate. Humility, not to mention being second, third, or even tenth best, is not something that Evans would have lived with, comfortably.

But the camera, the camera now, was fresh territory. And with the camera, he could grab his quick sketches of life, in pictures rather than words. Whatever interest he had in writing could not be sustained alongside his growing passion for photography.

Evans would later say:

Oh yes, I was a passionate photographer, and for a while somewhat guiltily, because I thought that this is a substitute for something else, well for writing, for one thing. But I got very engaged and I was compulsive about it too. It was a real drive. Particularly when the lighting was right. You couldn’t keep me in.

I can agree with Evans, that photography can quickly become a substitute for writing. One image can so easily convey information that may take thousands of words to do, and less eloquently.

A few weeks ago, when I started digging more deeply into Walker Evans’ life, I was asked by a magazine to provide a portfolio of photos, including any better quality digital ones. I asked Charles, a photographer who has worked with magazines in the past to give me advice on printing the photos, which he was very generous to provide. He also shared with me anecdotal stories about photography students preparing their portfolios, each professionally printed and bound

But I looked at my little digital images, all of them at 72 DPI, and my slides, and my nice, but not great inkjet printer and asked myself, “What the hell are you doing, Shelley?” just about the same time I read, …I was a passionate photographer, and for a while somewhat guiltily, because I thought that this is a substitute for something else—well for writing, for one thing….

And it is thankfully, and with relief that I gave up the nonsense about being a stock photographer for magazines, or an art photographer, or any kind of professional photographer, and return to what I love: writing. Because I am a writer.