Recovered from the Wayback Machine.

I recently finished a wonderful biography on Walker Evans: Walker Evans: A Biography by Belinda Rathbone. Some critics have said that the book reads a little too matter of fact to be interesting, but that’s a perfect type of biography for a man like Walker Evans–an objective biography for an objective man.

In the book I discovered that Evans was born in St. Louis, though he didn’t live here long, moving to Chicago, and eventually ending up in New York. He came from a dysfunctional family, was himself married twice, had numerous affairs, almost always with married women, and preferred rooms decorated in black, white, and gray. Additionally, I found out that he was not a particularly good student, kept flunking Latin, and always saw himself as a writer. Even after his photographic career was established, he saw himself as a writer, an interesting fact which I’ll get into in more detail in a later essay.

From the start, Evans rejected much of the contemporary style of photography that was prevalent in his time (and to some extent, still in vogue today). One style of photography popular with art photographers at the time was called pictorialism and rather than utilizing the power of the camera to capture images as is, featured created images that were contrived rather than found. You still see these types of photos today when a woman or man is posed holding an apple, looking pensively off into shadows, staged next to a carefully undecorated and plain white wall.

The second style popular at that time was modernistic photography, subjects of which are best described by a quote from M. F. Agha, art director of Conde Nast:

Eggs (any style). Twenty shoes, standing in a row. A skyscaper , taken from a modernist angle. Ten tea cups standing in a row. A factory chimney seen through the ironwork of a railroad bridge (modernistic angle). The eye of a fly enlarged 2000 times. The eye of an elephant (same size). The interior of a watch. Three different heads of one lady superimposed. The interior of a garbage can. More eggs…

One can see why Evans rejected both pictorialism and the modernistic photographic styles, but he drifted about for a time, trying to establish what type of photography he wanted to do.

It was after seeing a photograph by Paul Strand, of a blind woman with a hand lettered sign reading “Blind” hung around her neck that served as Evan’s inspiration. As Rathbone wrote:

The picture implied an encroaching crisis of the American dream of prosperity, but it showed no obvious emotion. The fact that the photographer had stolen his photograph was pointedly expressed by the stark sign hanging around the woman’s neck, as if the subject had come with her own caption. Was the portrait cruel or sympathetic? It was the fact that it was neither, that it appeared not to reveal the photographer’s feelings at all, that intrigued Evans.

…that it appeared not to reveal the photographer’s feeling at all. If there is any key to Evans, it is contained in that one sentence. In all of his photos, not once does he impose his view, his thoughts and feelings, between the subject and the audience. He disdained photos that deliberately attempted to manipulate the viewers emotions; particularly those that used sentiment, which he considered contrived.

The distinguishing component of all Evans’ work, was his objectivity.

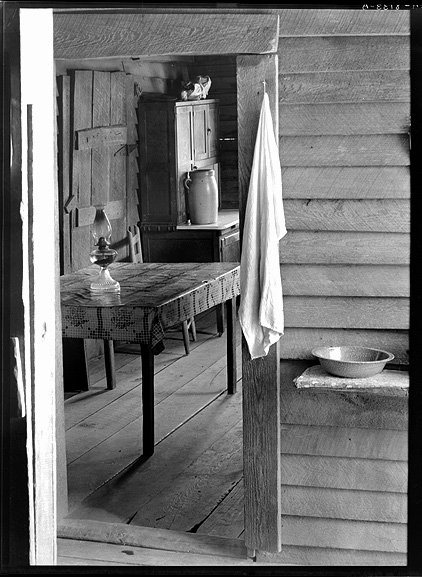

But Evans wasn’t just known for his objectivity and his excellent eye for an image — he was also known, or should I say, not known for his grasp of the mechanics of photography. He would ruin several images by his somewhat haphazard lab skills, and lose other images because of under or over exposure. It was not through knowing the mechanics of photography that Evans achieved his work; it was through his exceptional ability to see an extraordinary image from every day things; and then to patiently stalk that image, returning day after day, if needed, to capture it on film. He would never change the scene, or add or subtract elements from it. This, to him, would be completely dishonest. The most he would do would wait for a different light, or if he were taking photographs of people, wait until they were either unaware of the camera, or had relaxed from being in front of the camera.

Needless to say, Evans was almost always late in delivering on his assignments, and drove more than one person to distraction by his exacting nature. Lucky for us, he was not a conciliatory person.

In fact, one of my favorite Evans photograph (another one I can’t locate to reproduce here) was a somewhat blurry photo of Evans’ second wife, Isabelle Boeschenstein, wearing evening dress, hair in her face, lighting a cigarette at what looks to be some kind of gathering. It was not the photographic quality of the image that caught my eye; it was how much information about the woman was captured in that one simple photo. It is astonishing.

Evans did not rely on photographic tricks to make his images, and rarely did more in the darkroom then crop shots. But he was obsessed with how they were presented at shows, usually asking to hang his works himself, with no one else present. For the first edition of Now Let Us Praise Famous Men he was determined that the images for the book be perfect, and worked almost daily with the engraver to make minor adjustments to correct an engraving until it reflected the image he had of it in his mind. From Rathbone:

The wrinkles on the Burroughses’ bedsheets did not show up clearly enough; could he make them sharper? Could he show more clearly the tear in the pillowcase? Could he bring out the texture of the wooden wall and the objects around the fireplace? Could he soften the lines on Allie Mae’s face, sharpen the creases on Bud Fields’ overalls? Under Evans’ scrupulous direction, several of the plates had to be made over again entirely, while small imperfections in others were painstakingly corrected.

The engraver was too helpful at one point, and removed dead bugs from a photo of a bed, and Evans refused to allow the image be used as it was, and the fleas had to be added back in.

This reminds me of earlier discussions about the purists view of photography. Despite the care taken with the engravings for the book, Evans did very little with the actual images himself. Because of this, and his belief in photographs reflecting the image as taken–the true image–we would consider Evans a purist. I’m not sure what he would make of today’s digital cameras and Photoshop, though I have a feeling he would like the camera. So much easier to take those unexpected, hidden photos.

Earlier I published a link to a baby squirrel image that had been rescued from a mediocre photograph through the use of Photoshop. I have no doubts that this is not something that Evans would do.

No, if Walker Evans wanted a photo of a baby squirrel, it would be because he discovered the baby squirrel by accident one day and was struck by the image for some reason*. He would then get someone to hire him to take photographs of Native American wildlife, and would use the money to purchase new camera requirement, and probably to take other images in the neighborhood–the broken fence, the lost cat notices on the telephone poles, the old woman buying tomatoes at the market. He would then set up his camera by the baby squirrel’s hole, and if the baby didn’t oblige with the proper image one day, he would return the next. If a week goes by without the image, and by then the squirrel was too old, Evans would return the next year, much to the consternation of his employer (who he would still charm, even while irritating).

But by the time he was done, you’d have a rich, fascinating image of a squirrel, sitting in a hole of a tree, the grain of which would stand out in the image, almost as if the image was three-dimensional. The light wouldn’t be the proper light, it would be the perfect light, and the squirrel wouldn’t be enticed to pose–it would be acting as a baby squirrel acts, normally.

And it wouldn’t be a photo of an adorable baby squirrel, eliciting cries of, “How cute!” It would be a photo of a rodent.

*I doubt Evans would be interested in a photo of a baby squirrel.