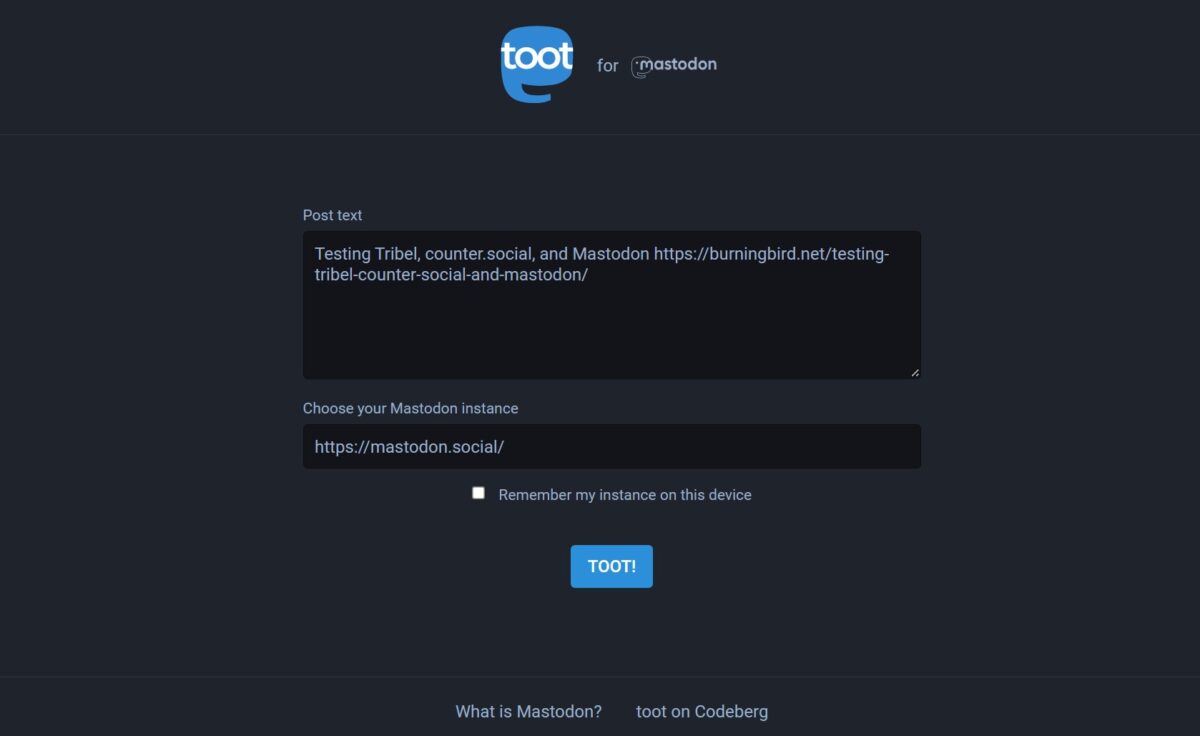

The social media upheaval continues but things are starting to quiet down a bit. Oh you can’t tell this from the media, which is full of stories leading with “Elon Musk says…”, but that’s primarily because the media hasn’t figured out how to wean itself off Twitter, yet. I quit Twitter the day that Musk […]