Cynthia Shelly released an alternative proposed HTML5 draft that addresses the table summary attribute. The responses to her draft have been less than edifying, and demonstrate rather succinctly most things wrong with the HTML WG.

If you follow along in the thread, you’ll see Apple’s Maciej and IBM’s Sam Ruby go back and forth on protocol, a discussion Maciej ends with a suggestion to focus on salvaging a “proposal” from the work. The thing is, providing alternative text in a specification is the proposal, the only that is deemed acceptable to the HTML WG. At least, that’s what we’ve been told in the past.

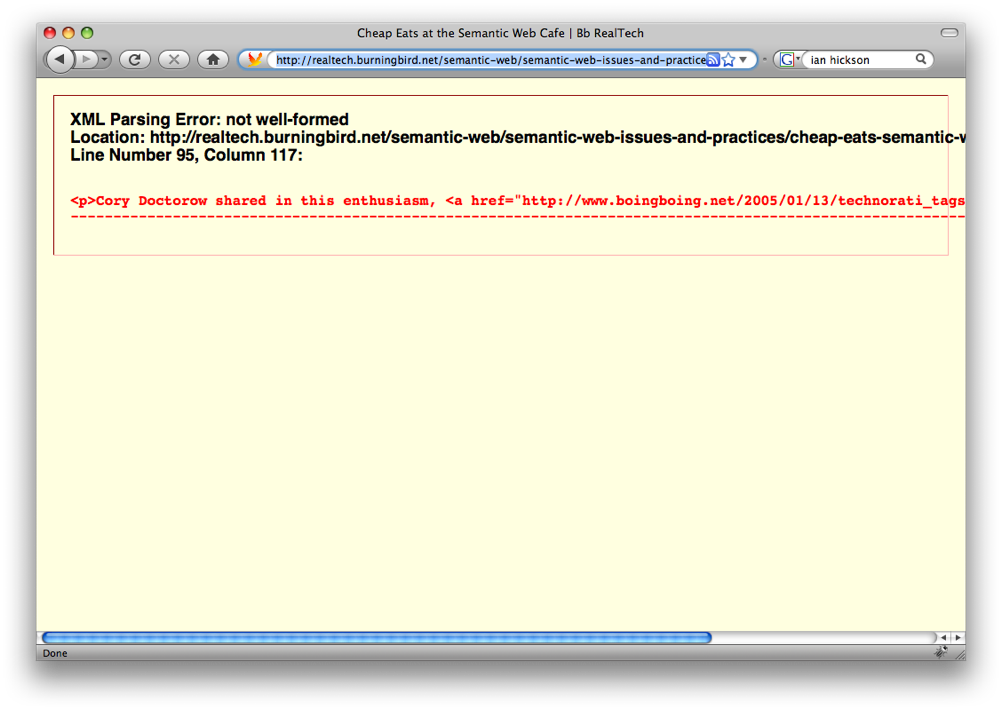

Not that Cynthia is demanding that the text be used as is. This was a suggested text, addressing how summary could be discussed in the HTML5 specification, in order to ensure proper use. The proposal also removes summary from the obsolete list. Cynthia proposed this alternative text in order to generate discussion, leading to its refinement; to encourage team effort. Simple enough to understand, but then we’re subjected to the typical Ian Hickson disingenuous approach to anything he disagrees with: pretend he doesn’t understand what the proposal is all about.

I couldn’t find any description of what problem this proposal is trying to solve. Could you point me to the description of the issue that is being resolved here? Why is the text currently in the HTML5 spec not considered acceptable middle ground?

It is difficult to evaluate proposals without understanding what problems they are trying to solve.

Incidentally, I believe the process that we are supposed to be following these days is that when there is a problem in the spec, a bug should be filed describing the problem, so that the issue can be tracked. If you could file a bug (or point me to the relevant bug if one is already filed), that would be very helpful.

(At this point I would like to inform my readers: everyone can file a bug, you don’t have to be a member of any W3C organization to do so.)

So, HTML WG team members are told by one of the HTML WG Chairs to provide alternative specification text, while the HTML5 author countermands such a recommendation, with a note that we file bugs, instead. Seriously, I keep expecting the third stooge to enter the scene, stage left.

And he does. The author of validator.nu, worker extraordinaire for Mozilla, Henri Sivonen, puts on his court jester cap to derail even the potential for worthwhile discussion:

Further quotes are from the proposed text--not from Maciej:

> Summary is one way to provide explanatory information about tables

> that consist of more than just a grid of cells with headers in the

> first row and headers in the first column.

>

Does this intend to say that using @summary is categorically

unnecessary when headers appear in the first column and/or first row?

If so, it would be good to make this clear.

> Such explanatory information should introduce the purpose of the

> table,

>

Shouldn't the purpose be stated to all readers?

> outline its basic cell structure,

>

Shouldn't this be generated by the AT from the table model?

> The information provided by the summary is needed by users who

> cannot see the table, but would usually be redundant for those who

> can.

>

This sentence sticks out as non-spec-like. It doesn't state a

requirement, so it looks odd in the middle of a paragraph that states

requirements.

> This must be done in a way that is associated with the table via

> markup, such that user agents and assistive technology can

> programmatically determine the relationship.

>

This sentence could make sense in WCAG-like contexts where things are

defined in terms of what available software happens to support. It

doesn't make sense in a spec that defines what software must support.

(Furthermore, "programmatically determine" is a special term from

other specs but isn't defined as part of the special vocabulary of the

HTML5 spec.)

The proposed text seems to imply (in the edits done on examples) that

having the explanation in a paragraph preceding the table isn't

sufficient without an explicit aria-describedby link (misspelled in

the proposed text as aria-described-by). Why is that not sufficient?

> When using summary in combination with another technique, authors

> must not use the duplicate text, but instead use summary for the

> parts of the description that are only useful to users who cannot

> see the table.

>

What about duplicating information that AT should be able to voice

based on the table model?

> <table summary="The table is divided into six columns: Map number,

> Date, Area or stream with flooding, Reported deaths, Approximate

> costs (uninflated), and Comments. The rows are grouped by flood

> types into six subcategories: Regional flood, Flash flood, Ice-jam

> flood, Storm-surge flood, Dam-failure flood and Mudflow flood."

>

In this case, the first sentence clearly duplicates information that

are trivially programmatically determinable by the AT from the table

model (given proper <th> markup). As for the second sentence, I think

it would be worth investigating if the salient content of the second

sentence is also realistically programmatically determinable from the

table model. On the face of it, discovering the content of the second

sentence from the table model doesn't seem like an overly hard

software problem.

So, the text of the proposal that Cynthia provides is addressed to humans, which Henri rejects, because Cynthia’s text should be addressed to machines. She discusses declarative markup, and addresses this discussion to people, in order to ensure that the summary attribute is properly used by web page authors and designers. Henri reduces the whole to algorithms, care and feeding of.

This is a perfect lead in to another discussion about HTML5 taking place elsewhere, in the W3C TAG, which has ultimate responsibility for ensuring the many specifications such as HTML5 work in a complementary manner for the web. The focus of the TAG at this time is detailing issues this group has with the current HTML5 draft, a discussion generating a typically mature level of discussion in the WhatWG IRC channel.

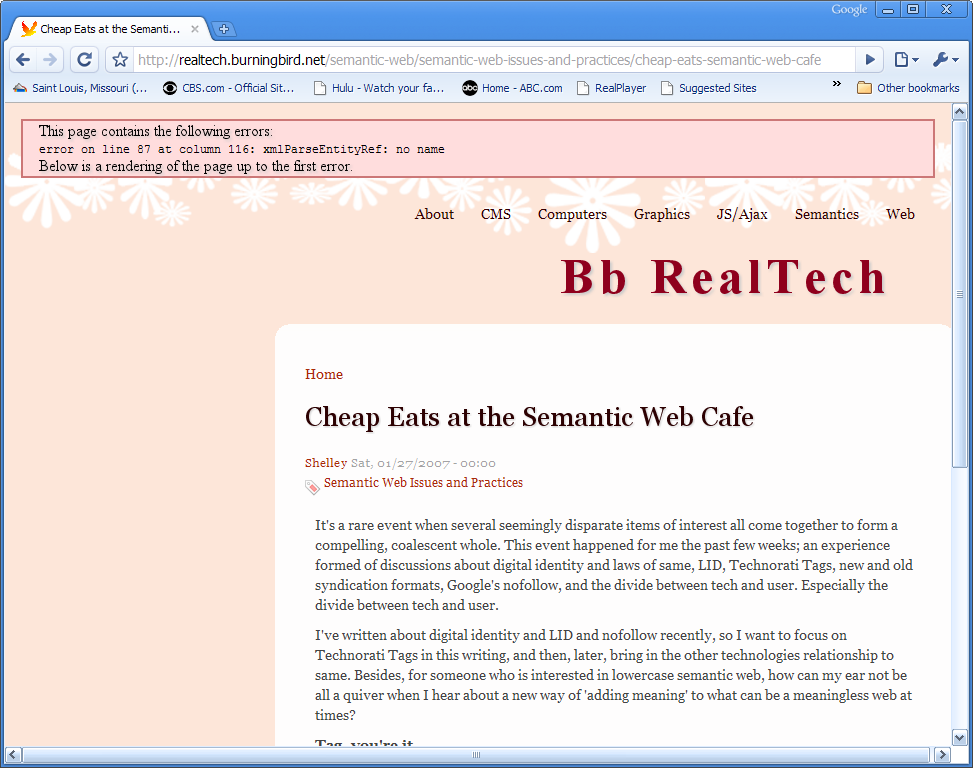

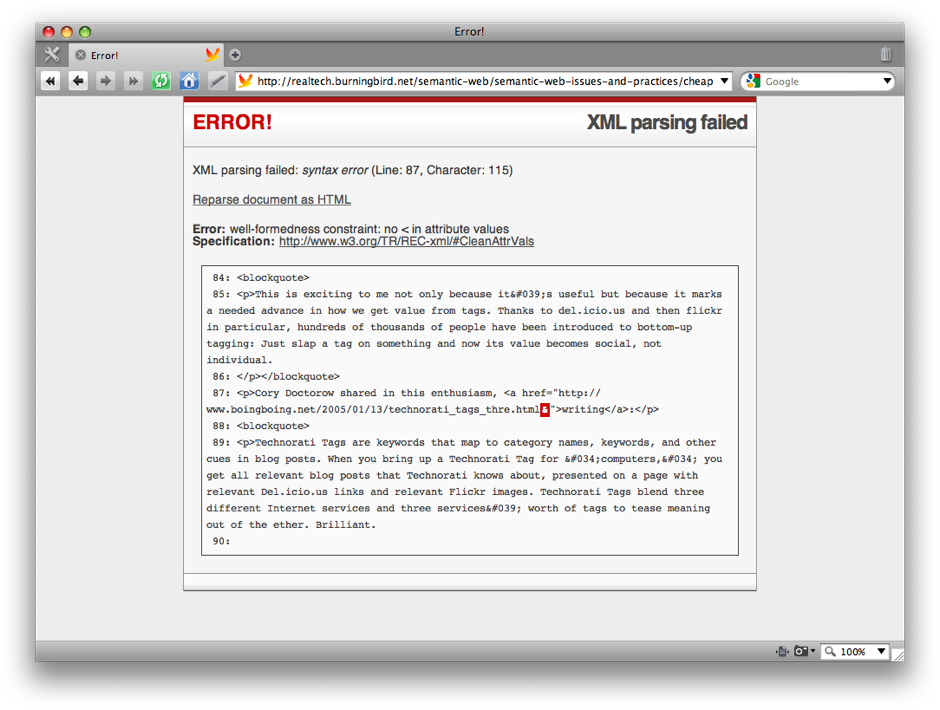

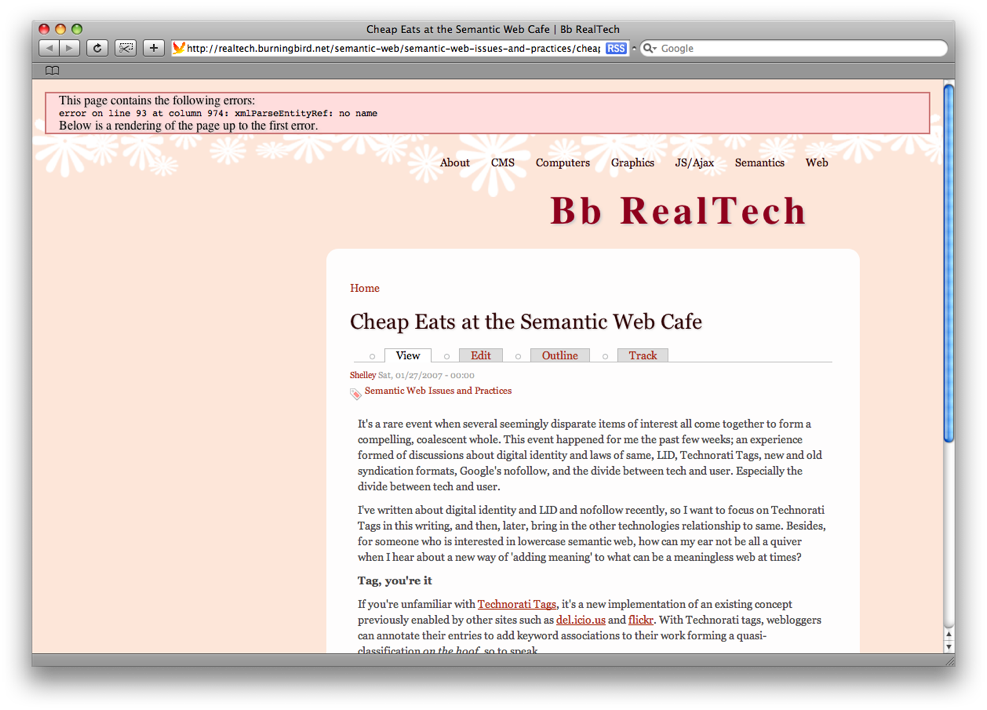

One such issue, as I have noted, as others have noted, is the fact that the specification is given in algorithmic terms, rather than as declarative text—based on discussions of a Document Object Model (DOM) with HTML markup given as a distant secondary item (barely covered, and leaving ripples of confusion in its wake).

The current rendering of the specification is considered more precise for the browser companies, for Mozilla, Google, Microsoft, Opera, and Apple, but the precision completely obfuscates the information needed by thousands, perhaps millions of web page authors and designers.

In the past, the main specification would be about the markup, with a secondary document describing the DOM. And oddly enough, this has worked, if we can believe the evidence of our eyes. Evidently, this wasn’t to the taste of the browser companies, who believe that it is more important that their needs be met, rather than the needs of the thousands, perhaps millions of web page authors and designers.

In addition, rather than leave many decisions up to the implementors of the specification, the editor’s draft seeks to detail, in minute detail, how everything is to be handled by implementors. Precise, very precise. Good luck with the 50,000 or so test cases.

So far, I have submitted three HTML5 bugs:

- When Web Workers was removed from the spec, orphan references were left – clean up is needed

- To remove the Microdata section, as it isn’t necessary, nor widely supported

- To allow other namespaced elements in SVG, since the use of these elements is valid within SVG

And I just submitted a bug for table summary. There will be others. Too bad I’m not one of the elite.