One of the many advantages of digital photography is that you can see what a photo looks like immediately. What happens to that great scenic when flattened out into two dimensions? And is that butterfly lost against the floral background? With this, you still have a chance to re-take the photo, if needed.

Still, there’s always room for the odd and even serendipitous image…

These images, as with most I show in my pages, reflect more or less the original digital image. I’ll usually crop the shots, and I may adjust the shadows and highlights if the picture is too contrasty. Or if there’s dust on the lens, I’ll use the fill tool in Photoshop to ‘erase’ it. In addition, I almost always sharpen an image after making a compressed version of the picture, and always before making a print.

I’m trying out a new Photoshop plugin set, Reindeer’s Optipix, which is said to have superior edge detection and sharpening. When I opened the edge enhancing filter, I was given options to set noise removing radius, and then edge sharpening radius before picking the amount of emphasis. Curious about the impact of these adjustments, I searched around for more detail. In one forum entry about the plugin, the reviewer mentioned that rather than an unsharp mask, which is a Laplacian of the Gaussian, the Optipix filter takes a Difference of Gaussians to enhance edges.

What a blast from the past this was. I remember studying about the Laplacian of the Gaussian (LoG) and Difference of Gaussians (DoG) when I did a college paper on David Marr’s landmark book on computational models of visual neurophysiology, Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. This book had such a profound impact on me that when I graduated from college, I wanted to work with computer vision (in addition to computational linguistics). Of course, when one only has a BS rather than a PhD, one goes to work with databases and FORTRAN rather than computational models of vision.

Still, I have my copy of the book today, and I think I even have that old paper somewhere. I remember when I wrote it out, on an old typerwriter, I had to hand letter in the formulae, and hand draw in the diagrams. My, haven’t we come far? Of course back then, I still had a fair hand and my writing was legible. Now, if it weren’t for my graphics tablet and pen, I’m not sure I’d remember how to hold a pencil.

To return to Vision, in his book, Marr explored various aspects of vision and with each discussed the physiology behind the act, modeling it mathematically, and then deriving a computational representation.

Consider edge detection. Our eyes have ganglion cells that respond differently to the presence or absence of light. ‘On’ centered cells respond when light is first introduced, and continue to fire as long as the light is maintained. Other ‘off’ centered cells respond only when the light is removed. Both actions are necessary to detect an ‘edge’ , which is really nothing more than a light area next to a dark or darker area–a difference of intensity of light.

(Think about tearing open a bag: one hand moves toward you, the other hand moves away and the action results in an effect–the bag opens, the aroma of potato chips fills the air. If both hands moved in the same direction, you’d starve.)

So how does a computer detect an edge? After all it doesn’t have cells.

Well, according to Marr and others of the time, one way to detect edges is to blur the image, and then subtract this from the original in order to determine the changes of intensity or zero crossings; leaving what Marr termed the zero-crossing segments–edges whose slope denotes the level of contrast of a an edge. Computationally, this is equivalent to taking a transform of the aforementioned Difference of Gaussians , and if you view a graph of this equation, it actually physically approximates how one would think of an edge if one imagined it one dimensionally–two steep hills with a deep divide between them.

For someone who alternated between love of mathematics, and terror of the same, Marr’s book was the first time I’d seen a real, rather than ‘accepted’ correlation between complex mathematics and the physical world. What made it ironic is that I didn’t meet this epiphany while studying physics or computer science. No, I was studying about the human visual system in the process of getting a degree in psychology

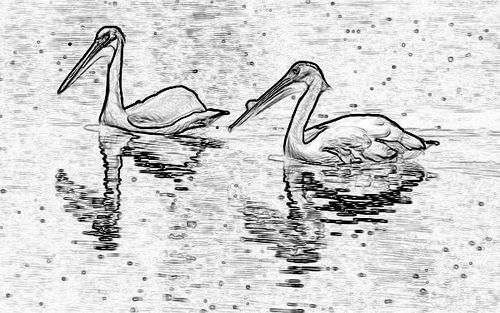

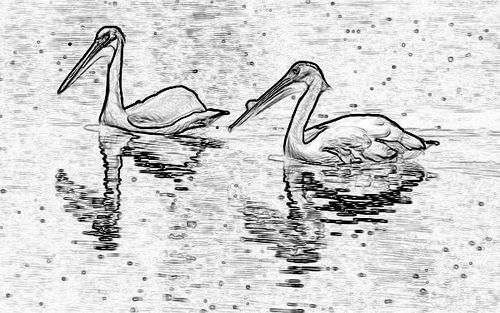

(A zero-crossing drawing, generated by Photoshop.)

Thirty years ago Marr envisioned a time when computers could see and wrote a book called Vision, published after his death of leukemia in 1980 at the age of 35. Five years later, I sat under a tree on campus making notes, and stopping from time to time to just stare at the bark, the birds against the sky, and the shadows the buildings made–crude hand drawings of which would make their way into my report on his research.

Five years later, in 1990, while I wrestled large databases for Boeing, a small company released a product called Photoshop that would incorporate work of Marr and others.

Fifteen years later, I sit with a thin, titanium computer on my lap, Marr’s book turned upside down on the chair’s arm, while I try a plugin downloaded over the Internet that does what I only dreamed could be possible twenty years ago.