The road to Alley Spring Mill is full of twists and turns, and I gave up watching the speedometer about the time when I realized there was no chance I’d be going over the speed limit. Most of the trees along the way were still leafless, and twisted, white branches mixed in with the short pine, only partially obscuring views of rolling hills, stretching out as far as the eye can see.

The Ozarks are old; old, and filled with vague memories of mountains that split this land, greater than the tallest peaks of the Cascades, mightier than the Rockies. So old that time has worn them down and softened their edges; carving the rocks scattered about, great boulders that once lay at the bottom of long, gone seas.

Small towns dotted the way with names like “Steelville” and “Eminence”, most still retaining both their original look and their vitality. Each was a pure slice of post-war prosperity, preserved for all time, except that Betty’s Beauty Salon is now The House of Tanning.

As the road crossed the many creeks and rivers that threaded the hills, it would shrink–at one time becoming a one lane crossing with warnings on both sides to “Yield to oncoming traffic”. I’ve wondered what would happen if two cars approached at the exact same time. Would they both slow until stopped, lost in a mix of politeness and caution? Or would the aggressive hit the pedal and the two cars collide mid-bridge? Then I thought of how little traffic I’d seen along the way and realized that the point was mute.

I had a headache when I started out on the trip. In fact, I have a headache most days, lately; and too many mornings being greeted by a face in frowns in the mirror. However, as I drove deeper into the Ozarks, the headache began to recede and I notched my speed up just a hair; just enough to add a swoop to the feel as I drove down the hills and around the corners.

I put on my own customized travel CD, the one with all the really good travel music. Listening to the mix of songs–”Born to Be Wild” between “Stop the Rock” and “Dueling Banjos”, “Gimme Some Loving” followed by “Queen of the Night” followed by “Rave On”–I edged the speed up just a tad more until I must have been going, my, close to 50. A wild woman on wheels, and mamas hide your sons! Wheee!

(Hot music is for hills. I save the soft stuff for the plains and the moody crap for the ocean.)

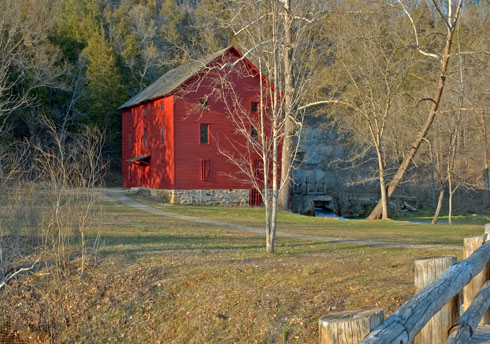

At the Mill I parked in the lot and grabbed my camera bag, but decided to leave my walking stick. It’s only a short walk on a path by the river to the Mill, and you can easily see its bright, red color against the dead winter grasses. However, it wasn’t until I was at the bridge over the creek to the Mill that I was able to see it’s surroundings, and I stumbled to a stop at the sight.

The water that rushed past the mill filled a hollow before flowing into the stream leading away. A trick of the light and shadow painted it a bright aqua color, as it foamed in a wide circle from the falls; however, as I got close to the water, I could see it was clear. Clear enough to see the individual tiny rocks at the stream’s bottom, and the bright green plants–watercress–that floated just beneath the surface.

The Mill was in a hollow, with steep limestone cliffs on the other side of the spring basin formed by the backed up water. In the cliffs, water and time had worn small pockets in the rock, forming caves just deep enough to leave the back wall in shadow.

I explored along the spring’s edge for a time, and then walked along the Mill back porch, right above the overflow gate. I was surprised at how fast the water was flowing and how much there was, especially this time of year.

I stared, mesmerized, into the flowing water until I noticed something white and wispy in the dark blue, at the gate where the water entered. It looked like a skeleton of a fish that had become trapped and died, with the force of the water stripping most of its flesh away.

A family walked by while I was lost in the waters, following a trail that cut into the cliff above the basin. I waited until the laughter and the sounds of their passing had died, and then followed. I wanted the place to myself, to savor the feel of the true Ozarks. It was a very intimate moment for me; I almost put my hand on ground, thinking I would feel the heartbeat of the mountain if I did.

The spring basin is an odd thing. According to descriptions, it’s 32 feet deep, and forms a funnel shape. It had a mirror like stillness, and the waters were clear, but you could only see so far down. A tree was growing out of the hill above the water in one spot, and underneath what looked like another tree had fallen in and become covered in green growth. It was eerie and I actually began to feel a little uncomfortable. Deep water has that effect on me.

But then, so do holes in cliff walls when I cannot see the back, and the trail I needed to take led directly between the two: lake and short, steep hill on one side; tall, pocketed and carved cliffs on the other. I desperately wanted my stick on the moment and I had no idea why because the only living things around were the birds, and I imagine cousins of the fish whose skeleton now decorated the Mill.

The path was wide enough for a family to walk side by side, but I teetered along the middle, equidistant between my twin fears of shadowed water and shadowed rock. I think if I had closed my eyes, I could have walked the path safely, the fear was that tangible. I wonder if this is how soldiers during war feel–held upright and kept moving by a fear of shadows; except for them, the monsters in the dark are real. If I were one of those soldiers, I think I would go mad; at the least, I would become numb.

The basin isn’t really big and the cliff mostly solid and I started to relax as I walked until I was, again, enjoying myself. I ended up stopping every few feet to take a photo of rock formations, the Mill, the stream, the Mill, and all variations of the three. The trail followed the spring as it headed to the river, with foot bridges to cross just after the basin and at the end of the park. I took the last one and then circled down by the spring, in the space between the bushes and the water.

I hadn’t heard anyone for a while, so I assumed I had the place to myself. Round a corner, though, was an old man sitting in a lawn chair by the river, ice chest by his side, sipping a coke. He wasn’t particularly remarkable looking: lined face, gray hair, and wearing a white shirt and jeans. I started to walk past, not wanting to break my need for privacy, but he called out “Nice day, isn’t it?” as I drew near, raising his can in salute.

Sighing, I stopped, and agreed that yes, the weather was nice.

“You know, you look tired and thirsty. Why don’t you stop for a moment, and have a cold coke.”

As he said this, he reached into the ice chest, pulled out a can and held it out to me. I was thirsty, and the pop did look good. I also thought it would be rude to just say, “No, thanks” and move along. Besides, I’ve found from past experience that people who sit and stare into water are usually people who have something interesting to say.

As we sipped our drinks, I asked if he was from this area, and he said no, he was born in Oklahoma and moved to Missouri after he served in the war. From his age, I thought he probably meant the Korean war, but he could have meant World War II or even Vietnam. I didn’t want to pry, though.

He asked how long I’d been in Missouri, and I said only a couple of years. He nodded, and said he could see that. I thought it was an odd thing to say, and asked him about it. He replied, that I looked a person who had found home, but wasn’t used to it yet.

I could agree with him, about finding home. Every time I visit the Ozarks, I feel as if all the worries of every day life just sort of fall away, leaving only peace and contentment behind. I even remarked on it, telling him I’d seen most of the country and some beautiful places, but nothing had the pull for me that Missouri did.

He nodded his head in understanding, and said it was because I had a “…grain of Missouri dirt buried deep inside”. A grain of Missouri dirt buried deep inside? Seeing my puzzled look, he chuckled and said it was an expression he picked up from a story his Dad used to tell him when he was a kid.

According to the old man, his father used to tell him of a time, many years ago when the earth had cooled, the grasses in the plain had sprouted, and people were ready to be born. The spirits of the earth (“or angels, if you prefer”, he said) each grabbed up a handful of dirt from all around the plant and then tossed it high into the air. Higher than the mountains the dirt flew, until it was captured by the Winds that blew around the world. In the Winds the dirt became all mixed up, until a speck of Paris dirt was alongside one from Hawaii, and one from China next to one from South Africa, and so on.

As each person is born, a speck of this dirt falls to the earth and becomes embedded, deep inside them, at the very center of their being. This speck, this land of their soul would stay inside the person all their life. Then, when they died, at the very moment after the last breath, the spirits would gently retrieve it, and toss it back into the wind.

(“My Dad swore he saw this once, when my great aunt died, but I think he was pulling my leg. Made my mother angry, though; she thought something was wrong with me when I told her I wanted to go to the hospital and watch people die.”)

Now, the speck of dirt a person gets could be from the homes of their birth, and some people live their whole lives being content to stay in one place. Most folks, though, are born with specks of dirt outside their homes, and this leaves them with both a curiosity and fascination with faraway lands.

Not all can travel, though, and those who can’t eventually grow to appreciate the land where they live, but never with that strong pull that you find between a person and the land of their soul. Even among travelers, most will never find this land, but for those who do, the attraction may defy both reason and understanding.

The land pulls them, pulls at the speck of dirt within them, trying to reclaim that bit of itself lost long ago. And if you ask the people why they love the land so much, most of the time they’ll say that they feel like they’ve come home

Over time as some of the specks are claimed and reclaimed by people who never find their lands, they change, become less defined, as if all that bouncing about brushing up against strange places rounds the edges. People who get these specks seem to be happy wherever they are, even if it’s a tar hut in North Dakota. (“And I’ve lived in a tar hut in North Dakota; you’d have to be crazy or a priest to be happy in a tar hut in North Dakota.”)

Others, though, are born without any speck at all and this is a great tragedy. It’s like a piece of their soul is gone, leaving them always hungry, always wanting and reaching for more in an effort to find what they never can. They may end up rich and powerful and even leaders of many nations–but they’ll never be happy, and they’ll never be content.

“So that’s why I said that you must have been born with a grain of Missouri dirt”, the old man finished. Enthralled I could only nod my head in agreement. Of course, makes sense. I have Missouri dirt inside. That explains why I hate Los Angeles–no affinity to my dirt.

I thought, though, on those moments of fear I felt of the shadowed caves and the deep water; of the time when I was lost in the woods; and the other time when I wouldn’t walk into the crack in the ground at Pickle Creek. I didn’t want to tell man I was afraid of a little water or a rock formation, but I did tell him I have had moments in the Ozarks when I’ve been afraid. I asked him wouldn’t the land of my soul be a place where I wouldn’t be afraid? Where there would be no fear?

“Live in a place without fear? Why would someone want to live in a place without fear,” he laughed at the idea.

“What would be the fun of that?”

I’d finished my pop and since it was getting late and I still had a four hour drive home. I thanked the old man, both for the pop and the wonderful story and headed back to my car. Once there, as I was putting my photo pack in the back seat, I noticed that I did have a bottle of water in the bottle pocket. Must be getting old, I thought, to forget I’d brought water.

I started the car and rolled the windows down because it was warm and I wanted to enjoy the smell of green in the air. As I was driving down the lot to the exit, though, I noticed that there were no other cars. I slowed down and stopped and looked carefully around, but couldn’t see any other car but mine.

It was just like that time at Elephant Rocks, when I came upon that guy who was stopped by the side of the path, gazing into the quarry pond; except that one told me the story about his dad and quarry mining. On that day, too, I remembered there was no car other than my own in the parking lot when I left.

A cool breeze blew in the open window, causing me to shiver, and I rolled the windows back up.

What would be the fun of that, indeed.