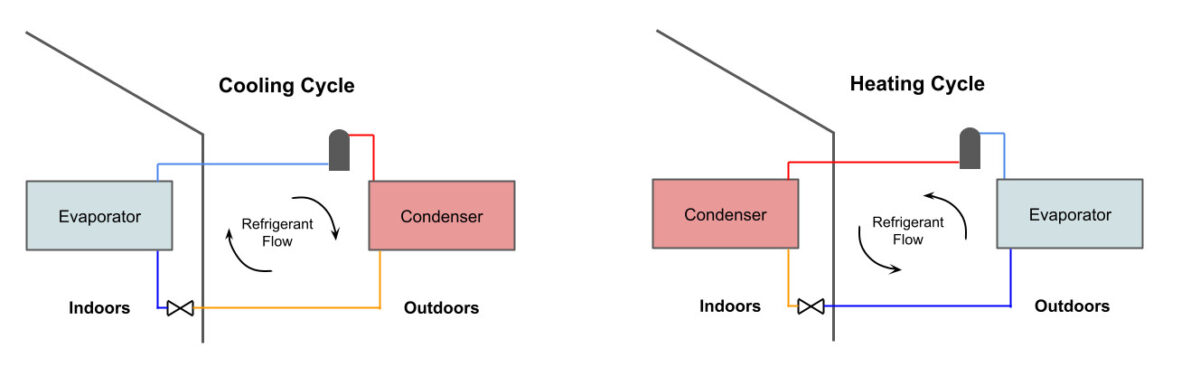

My friend Simon St. Laurent posted a video on Facebook that goes into the mechanics—and efficiencies—of a heat pump.

Homes in Savannah are primarily cooled and heated by heat pumps. The house we bought had a 2.5 ton unit, with the interior portion in the attic. Being new to HVAC systems installed in the attics, we weren’t familiar with the important rule to these units:

You have to treat your condensate pipes at least 4 times a year for them to remain unclogged at all times.

It wasn’t until we saw water dripping down the wall from the air intake vent that we realized we had a problem. Water had been collecting in the plenum (that’s the piece that holds the HVAC in a vertical system and provides duct attachment) and badly rusted it. The cost to replace the plenum was enough, and the system only a few years shy of replacement, so we decided to replace the system with a new one.

For the size of the unit, I performed my own analysis using the extremely difficult to use Manual J calculations and determined we really needed a 2.7 ton heat pump. Because of the smaller size, our unit was running for longer periods of time, but it also wasn’t short cycling—the unit wasn’t turning on and off too frequently. Short cycling is the death of an HVAC unit, which is why HVAC companies typically recommend a smaller unit if your home needs fall between unit sizes. Still, constant running isn’t highly efficient, either.

When we bought our new unit, we went with a 3-ton unit, which normally would be a little too large for our smallish house. However, we also bought a multi-stage rather than a single-stage heat pump. Specifically, we bought a 5-stage heat pump from Carrier.

A multi-stage heat pump doesn’t just run on and off, it also runs at lower capacities, with matching lower speed fan. The unit runs longer, but uses less energy because it’s running at a lower speed compression. You also don’t get sudden blasts of high heat or freezing cold that you would with a single stage heat pump. And you rarely hear our unit because, for the most part, it runs at stage 1 or stage 2.

We could have gone with a full ‘infinity’ stage unit, with an infinite number of stages, but our small home and smaller unit size doesn’t justify the additional expense. We could have also gone with a two stage unit—a very popular option—but I liked the idea of the unit being able to run at even lower speeds than what you normally get with a two-stage. Our system can run as low as 25% capacity versus the typical 70% capacity you get with a two-stage.

Unlike single-stage heat pumps, you don’t set cooling temps uncomfortably high and heating temps uncomfortably low in order to save on energy use. The real key is find your comfortable temperatures, but when you vary them throughout the day, do so gradually. When you change the temperature by one degree, the unit is able to power down but still meet the new temperature demand. With the smart thermostat we bought, the unit actually anticipates the temperature change and begins to gradually cool or heat to meet it.

We’ve had the unit for one year and I did an analysis of *energy use for the year. I found we used 17% less energy than the previous year. This doesn’t seem like much until you consider that we’ve set the house for more comfortable temperatures, especially in the hotter summer. In addition, we had a hotter summer in 2022 over 2021, as well as a freakish period of below 20 degree weather this winter. (We used a base heater in the garage during the subzero weather to keep garage pipes unfrozen. Without this demand, our energy use would have been 19% less for the year.)

I estimate the new unit will pay for itself in energy savings within 5 to 7 years. The savings will pay for the higher cost of a multi-stage system within two years.

Heat pumps aren’t for everyone. But unless you live in the frigid north, keep them in mind the next time you replace your HVAC. And if you get a heat pump, get a multi-stage unit.

*Only compare energy use, because electrical companies tend to screw with costs throughout the year.