Visiting Scovil’s web site to once again look at and admire his photographs of minerals, I discovered the name of the green mystery mineral I discussed yesterday. It’s Vivianite.

It’s not a perfect sample, but at least it’s not blackened as so many Vivianite samples are with exposure to light (she says as she looks at her sample, sitting in the sun). Obvious holes in the matrix show where better crystals have been pried loose, probably to be sold separately. Personally, I think imperfections in the piece adds to its character.

I have always collected based on beauty and character rather than value and perfection. Because of my undisciplined approach, my collection is interesting rather than profound. That’s not to say that the collection isn’t worth money — sometimes beauty and character do go hand in hand with monetary worth, as demonstrated with this virtually flawless rhodochrosite.

Still, there are a few of my samples I shouldn’t include in the collection photos because they’re obvious fakes, or novelty items and of no serious value. When you show your collection, you don’t show these rocks. You certainly don’t photograph them.

Mineral collectors will only show you their good pieces, the ones they’re most proud of. However, if you look into their dark corners and hidden drawers, you’ll find their bits of fraud, fiction, and flaws — samples they think about tossing someday, but they won’t. The imperfect pieces, the mistakes, and the fakes add life to a collection. They add history. They make a collection interesting.

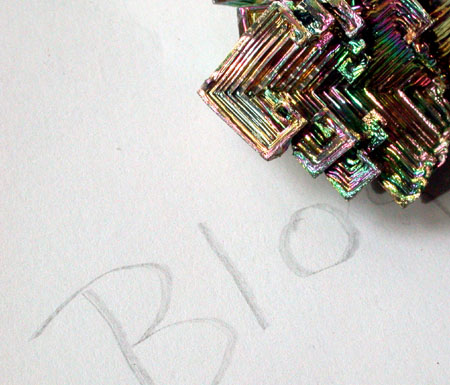

For instance, the photo below is of bismuth, which is normally a featureless blobby white/grey mineral. However, put it into a centrifuge, spin it at fast speeds and inject a little oxygen, and viola — you have a beautiful bit of color. No value to it, but I like my eccentric no value pieces. This particular one reminds me of an Escher drawing. You can also use it as a pencil — now, how handy is that?

I have a few frauds, too. My favorite is a hand-sized rock with quartz and appetite crystals in it. I have no doubt about the nature and quality of crystals, but the sample itself is an obvious fraud. I knew it was a fraud when I bought it. I still bought it, and therein lies the value of the rock.

At an outdoor mineral show consisting of tents set up in the parking lot around a rather seedy motel in Tucson, Arizona, I came across one table filled with yellow-green appetite crystals from Mexico. Most were still attached to their rust-red matrix, making the pieces quite pretty overall.

I tried to effect a knowing attitude, but I swear, I must have had rube tattooed on my forehead. The Dealer, an older man who was very gallant to me and kind to my niece (not all that common among the tents if you’re not buying in bulk), sized me up, came to some kind of internal decision, and brought a rock from underneath his table for me to look at — a hand-sized piece with a couple of relatively nice appetite crystals in it.

“That’s what you want”, he said in heavily accented English. “That’s good rock. Nice crystals. I give you good deal on it.”

I picked up the rock and looked more closely at the two larger crystals. They were both wedged into the rock but even a cursory examination showed that the crystals were cut at the bottom and then glued into the rock, with bits and pieces of broken crystal glued around them in an attempt to hide the obvious manipulation. (Crystals in matrix always sell better than those that are loose.)

I looked up at the dealer and he beamed at me, nodding his head, pointing at the rock and kept saying, “Good rock, nice crystals, eh?”

“It looks like the crystals have flat bottoms and aren’t attached to the rock”, I said.

“No, no. This happens sometimes. Pressure on rock force crystals loose, but they held in by rest of rock.” He assured me, shaking his head a modest display of genuine sincerity. “No, this is good rock. Good crystals. I give you good deal.” Pause.

“Fifty dollars.”

I gaped at him. Literally gaped at him, mouth open in astonishment at the chutzpah of the dealer. I held the rock in my left hand, and pointed at the crystals with the index finger on my right hand and just looked at him.

He smiled back, beaming in pride of this treat he was bestowing on me.

“Fifty dollars?”

Beam.

“Are you kidding? This is a fake!”

His smile faltered. A hurt look entered his big brown eyes (before, bright black and alert, now suddenly taking on aspects of one’s favorite dog just before it dies). His age set more heavily on his shoulders and he shrunk in slightly, as if in despair. His body said it all: His son has died; his daughter has run off with a biker. I even thought that, for a moment, I could see his upper lip trembling, and a hint of moisture appearing in the corner of his eye. I watched his change of expression — from certitude to dejection — with utter fascination, and more than a little consternation.

“Madam,” he said quietly. “You wrong me. This is no fake. Please, I would not do such a thing”

Placing his hand over his heart, he lowered his head slightly and pulled away from the table, turning his shoulder away from me as if flinching from a blow. I looked back at him and I realized in that moment, I have met fraud before, but I have not met artifice. And artifice is a ceremony, as precise as the tea ceremonies in Japan — my response was equivalent to not taking off my shoes, spilling the tea, dropping the cup, and then farting when I go to pick up the pieces.

I didn’t know what to do. Putting the rock down and walking away would have flawed the moment and marred the experience, for both me and my young niece who was with me that day. But I didn’t know how to recover.

“I, uh, I’m sorry,” I stammered. “Uhm…I didn’t mean to..uh”

The dealer was not a cruel man; or perhaps he was used to dealing with gauche Americans who buy their goods marked with barcodes and stickers, with heavy assurances of quality. He turned towards me, his face now that of one’s favorite wise old Uncle, the one mother invites to dinner but then hides the booze.

“Madam, I understand. There is so much evil in the world. You must be careful. But see now, I am an honest man. But I am not a selfish man. I will give you this rock, this pretty rock for … forty dollars. It is a steal at forty dollars.”

Shrewd eyes on my face. Next line was mine. I had my opening. I could have put the rock down and say that I hadn’t that much money and I still needed to buy lunch for my niece and thanked him and walked away and the moment would have been salvaged, but it wouldn’t have been right. Besides, the crystals were good if small, and there were some interesting bits to the piece, not counting the ingenious use of glue.

“I’ll give you ten dollars for it.”

“Madam! Ten dollars! You are joking! No, no. Ten dollars. No, no!” He exclaimed in dismay, but he also smiled at me in approval of my response — there was hope for me yet, me with my wits dulled by years of supermarket shopping and sell-by dates.

“Thirty-five dollars. I will take thirty-five dollars.”

I was about to counter with fifteen, feeling more confident in this bargaining game when the Dealer picked up another crystal on the table — a small one. A very small one. Barely more than pretty dust.

“And I’ll throw in this lovely crystal for your niece. See? It is a fine crystal. Yes? Good offer?”

“That’s very kind of you,” I said, clenching my teeth at the exclamations of delight from my niece who loves getting something for free even more than she likes sparkly things that cost money.

Artifice.