Archived with comments at the Wayback Machine

Dan Gillmor wrote about the following in today’s eJournal:

Obviously we need to find out what went wrong, if we can, before sending the shuttles back up. But I fear this accident (assuming that’s what it is, as is almost surely the case) will instead be a justification for paralysis — a halt to U.S. space exploration when the proper response is to redouble humanity’s push into the frontier. It has never been more critical, given the terrestrial threats, to get the species off the planet and to find new resources for those who remain.

The space station and shuttle program were under fire for other, good reasons. They do little for true exploration of space. A reexamination of the entire space program — and maybe turning it into a truly global affair — would be smart at this point.

Dan has the view of so many people who are impressed by the grand acts of space exploration — acts such as landing on another body in space — when the greatest acts of discovery have been through our eyes, not through our feet. And it is through our eyes, with the aid of instruments carried by the shuttles, that we’ll continue to learn in the future.

The Shuttle Discovery carried Hubble into space, and through Hubble, we’ve discovered stars being born, and brown dwarfs, and nebula of such beauty that they put the greatest artists to shame. It is through Hubble that we have discovered worlds in other galaxies.

The Shuttle Columbia, the very ship we lost today, carried Chandra into space, and it is through Chandra that we’ve begun to learn about that greatest of mysteries, the black holes of space — the keys to the beginnings of time and light and life, itself.

It is through the experiments conducted in space aboard the shuttles and the space station that we’ll learn so much about the life on our own planet. About ourselves and our place in this huge universe.

When we flew to the moon we discovered rock. And when we fly to Mars we’ll discover more rock, and maybe a little water. But we’ll find life through the instruments launched and maintained by the shuttles; shuttles managed by the crews who never have a chance to step onto another world, but who quietly work to give all of us a chance to see deeply into space and to peek at other worlds. Crews such as those of Columbia, who risk their lives with never the hope of a mention in history, or a parade down the streets of New York.

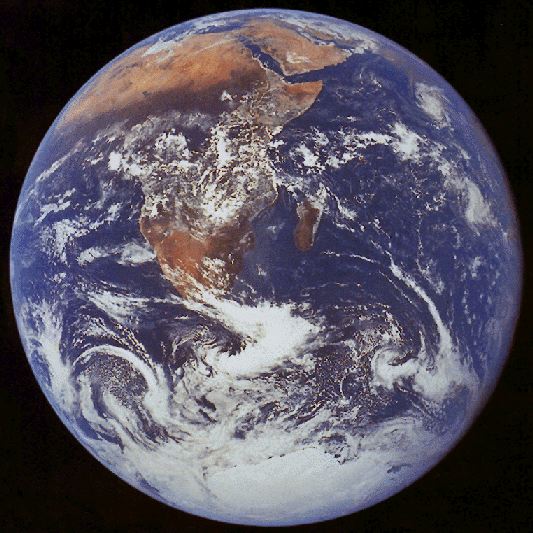

Most importantly, though, it is because of the shuttles that we have a better view and understanding of what I consider to be the most beautiful world in the universe — a blue and green and gold and brown and white marble that hangs in the blackness of space. A world we call Earth.

This is our home, and most likely will always remain our home. As much as we might wish to use all of it up and then jet out to a new home — pulling feats of terraforming and travel faster than the speed of light miraculously out of our scientific hats — we must accept the fact that our ability to destroy, pollute and exhaust far exceeds our ability to make new scientific discoveries that will enable us to travel to other galaxies. Thanks to the efforts of the Shuttles, we better understand our world. Maybe someday, we’ll even learn to appreciate it.

I agree with Dan on one thing: space exploration should become global. But I have to disagree with all my heart when he says that we’ve had little true exploration of space with the shuttles.